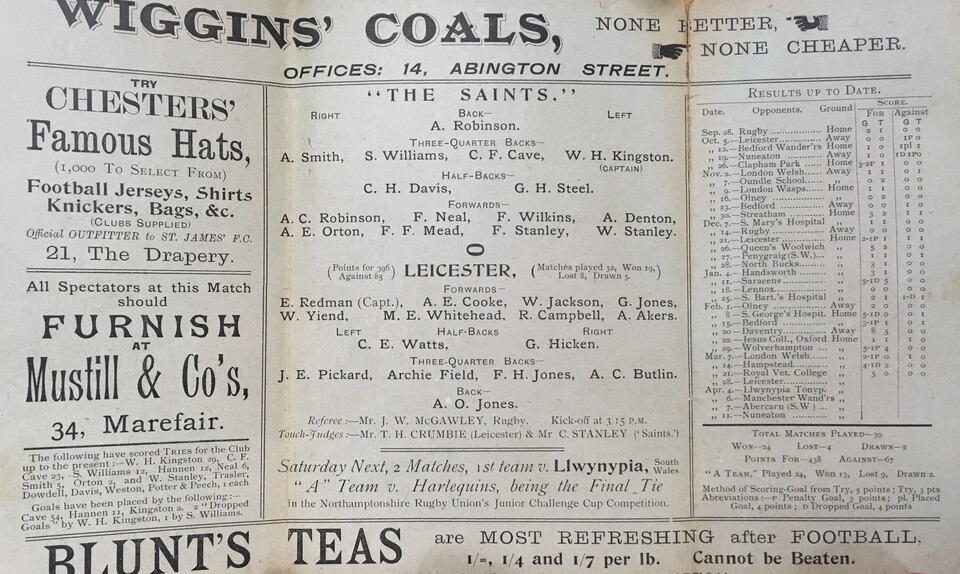

Ahead of this weekend’s East Midlands Derby, Club Historian Graham McKechnie takes a stroll down memory lane with a profile on Saint #74, Archie Field, one of the first players to make the switch between Saints and Tigers…

Northampton Saints and Leicester Tigers met at Franklin’s Gardens 125 years ago for the eighth East Midlands Derby.

It was the third time they had met that season – Tigers winning at Welford Road before Saints won at the Gardens. Both clubs found themselves with a Saturday free in March so hastily arranged a decider.

As many as 5,000 people turned up at Franklin’s Gardens for the match, despite ‘tempestuous weather’, all set for a 3.15pm kick off. Much to their annoyance, two of the Leicester team missed their train, pushing the kick-off back to 4pm. Luckily the Northampton Temperance band was on hand to keep the restless natives entertained.

Saints won 5-4 that afternoon. The conditions were difficult, and the pitch was heavy, which accounts for the low scoring (and why Saints’ captain, Billy Kingston, had to change his muddied shorts midway through the second half). Despite the weather it was an afternoon of ‘indescribable enthusiasm’ – Northampton winning the match when Charles Cave converted his own try.

Despite both teams being slightly below full strength, several interesting names leap out. This was a widely-admired Saints team – like Tigers just sixteen years old, but starting to make a name for themselves nationally. Albert Orton, one of the founder members in 1880, was to be found in the pack, along with other formidable players now forgotten; Neal, Mead, and Wilkin.

Archie Field missed several long-range attempts at goal for Leicester in the match. Of all the players involved on that cold spring afternoon, he is perhaps the one of most interest, because Field was one of the earliest players to have played for both Saints and Tigers.

Even after well over a century, there is more than a whiff of professionalism about Archie. He was a shoemaker from Olney by trade – coming through that club like so many other Saints players over the years. The Bucks Standard tells us that, ‘the excellent training he received with the Olney Club enabled him to become one of the finest three-quarter backs of his day’; the Northampton Independent said he was, ‘one of the greatest footballers that Olney ever produced’. After several seasons with Saints, in 1896 Field switched to Leicester (where he was a ‘shining light’), spending two seasons there before seeing sense and heading back home to Saints and to Olney.

Any suspicion about Field’s professionalism came out into the open in 1898 when he crossed the great divide. It is difficult for us to understand the depth of hostility to professionalism and to rugby league (or the Northern Union as it was then known). It was only three years after the game split and if you went over to professionalism, you were persona non grata in union. Officials hunted out agents and professionalism with a determination which bordered on obsession. Northern Union agents targeted clubs like Saints – poor Billy Patrick, a Saints scrum-half, was barred for life after signing for Bradford – not that he ever played for them, it was said he signed to stop an agent’s relentless pursuit of him.

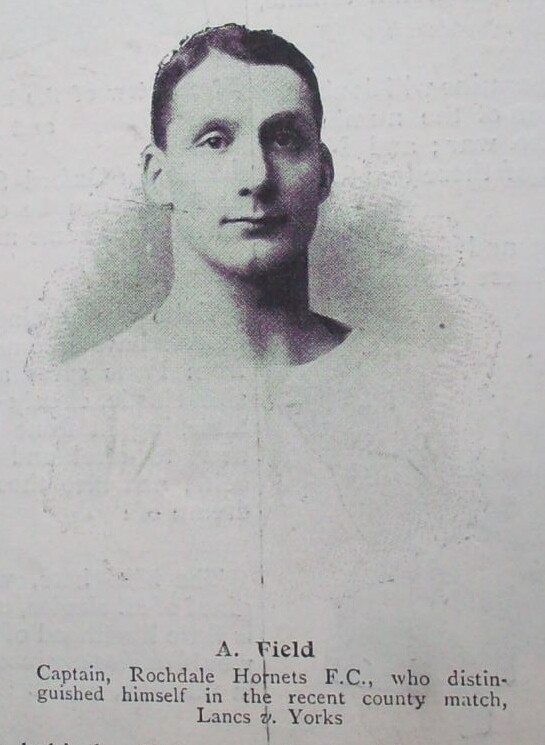

It was in an era of suspicion and hostility, but a working man like Field ‘embraced professionalism and threw in his lot’ with Rochdale Hornets, one of the founder members of the Northern Union. He made his professional debut on 10th December 1898 and proved to be as successful in league as he was in union.

He was, according to the Rochdale Observer, ‘was one of the best centre three-quarters the club ever had….Field was adept at opening out the game and his play always appealed strongly to the spectators. He was a very popular player.’

In addition to playing for Hornets, he also represented Lancashire in their prestigious and keenly-fought cross-Pennine matches against Yorkshire, and was landlord of the Duke of Wellington Hotel in the town.

His Rochdale career lasted three seasons before he headed back to Olney, to work as a boot-laster in Hinde & Mann in the town. He could not, of course, play rugby union ever again, but instead turned out for the town’s cricket and football teams.

In July 1916, at the age of 42, Field was called up to join the army – concealing his age so that he could serve. He was placed in the 2nd Battalion, Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry (2/Ox and Bucks) as a private. Field was trained as a Lewis machine-gunner and was soon in action, fighting in the dreadful mud and misery of the last days of the Battle of the Somme.

In the spring of 1917, the battalion was moved north to be part of the Allies’ latest offensive around Arras. They went over the top at 4.25am on 28 April, near the village of Arleux. It was a depressingly familiar story; heavy shelling and gun fire, insufficient artillery support and uncut barbed wire. The officer writing in the battalion war diary expresses his frustration that there weren’t enough stretcher bearers to deal with the large number of casualties.

Archie Field was one of them. Wounded on 28th April, he died two days later at a field hospital and is one of 2,778 men buried at Aubigny cemetery.

Any hostility Saints’ officials may have felt towards the ‘pro’ Field was forgotten. His name rightly sits alongside the other eleven on the War Memorial. His wife, Sarah, was left to bring up their three children – the eldest of whom, also named Archie, went on to play for Olney. And in 1922 the family was back at the Gardens, as Sarah laid a wreath at the memorial’s unveiling, to remember a brave and beloved husband and father, and an important man in the history of both of these great East Midlands clubs.